When we enable developers to create page or API monitors, we want to automate as much of the code writing process as possible, so that developers can test the functionality they care about without getting bogged down in setup steps.

To involve developers in monitoring, you need to make it easy

Most engineering organizations are shifting their monitoring and observability left, making developers part of the team that makes sure their service is always running and available. But we don’t expect our developers to become QA and Operations experts, so we need to enable their contributions with as much automation and default configuration as possible. The goal of this guide is to help create an easy process for all your engineers to contribute to monitoring. Just like any Checkly user, developers can still control every aspect of how a monitor runs, when it detects failure, and who gets notified of that failure. This isn’t about taking away control, just setting defaults and automation so that you don’t need to become a monitoring expert to contribute to your team’s monitoring.

This guide will tie together material from our Playwright Learn articles, our blog, and our tutorial videos, to help you create an environment for developers that makes it easy for them to add new page checks with minimal repetitive code. We’ll cover:

- The Checkly CLI and Monitoring as Code for developers

- Creating standardized configuration for checks and groups of checks

- Automating repeated tasks like account logins so the code can be re-used in multiple checks

- Adding standardized code that runs with every check

Whom this guide can help

This article will refer repeatedly to an ideal “developer” who understands their own service quite well, but isn’t experienced at at either QA or monitoring. They may not be an expert in the automation framework Playwright, which we use to write our monitors, and they don’t have experience with specific configuration like retry logic, alert thresholds, etcetera. This guide can also help you make monitoring accessible for:

- Front-end developers who work on the user experience, but haven’t previously monitored the site in Production

- Integration engineers who want to make sure that changes to third-party services don’t break your site

- User Experience engineers who want to make sure everything works as expected for all users

Though the rest of this guide will refer to our developer as the person we’re enabling, feel free to slot in anyone who we want to enable to write monitors, without requiring they become experts in Observability, Monitoring, Checkly, or Playwright.

The Checkly CLI and Monitoring as Code for developers

First off, our developer may not be very excited to log into a web interface to create new monitors. Since developers are used to running and deploying code from the command line, we want to make available the Checkly CLI to our developers. A full guide to the Checkly CLI is on our documentation site, but in general the process would look like:

- Set up the CLI on the developer’s machine - install is easy with npm, then the developer can authenticate their cli with

npx checkly login. - Create a new project - developers can either grab an existing repository with the team’s checks, or use

npm create checklyto make a new project. - Run your checks - rather than running new Playwright checks from the developer’s laptop, they can run checks through the whole Checkly system with

npx checkly test, the tool will scan the project for tests, run them as configured from the real geographic locations, and give a local report on results. - Deploy your checks - Once the developer is happy with their checks, they can deploy them with

npx checkly deploy, and they’ll show up for all users in the web interface.

For small teams just getting started with Checkly, this is all you need to do to harness the CLI for your process, but as you grow you’ll want to have a single source of truth for the code of all existing checks, and if necessary a change review process, for that you can use the Monitoring as Code model by storing your checks and their configuration in a shared repository.

Grouping Checks and Standardizing Configuration

It’s a great feature of Checkly that any check can have totally custom settings for every aspect of its running: it can run at a custom cadence, from its own geography, with its own logic for retries. This means that if, for example, you’re creating a new test specifically to check localization settings, you can set just that check to run from dozens of geographies, even if most checks only need three or four.

Of course, we don’t want to give our fresh developer over a dozen settings that she needs to set just to create her first check. New Checks created either in the web UI or from your code environment via the CLI will default to using the global configuration. You can view and edit this global config in checkly.config.ts, you can see a reference on this configuration and options under the project construct documentation. Some suggestions for default configuration:

-

Set a generous

RetryStrategy! Some failures can look extremely worrying even if they happen once, but it’s worth double-checking that the problem wasn’t entirely ephemeral. Full documentation of retry configuration is on our docs site. -

If you’re encouraging microservice developers or frontend engineers to add checks, consider setting the default frequency to be relatively low. It’s great to test edge cases or unsual scenarios, but someone without exposure to Operations is unlikely to need to run a check every minute.

-

Make sure your geographic

locationsreflect your userbase. You can userunParallel:falseif testing from a large number of locations, so that checks will run from a single location each cycle.

Check Groups and Alert Policies

You may want to go beyond global settings for a larger or more complex team. For example if a group of engineers is working with:

- Different notification expectations

- Different URL’s and other check variables

- A specific set of features in your application

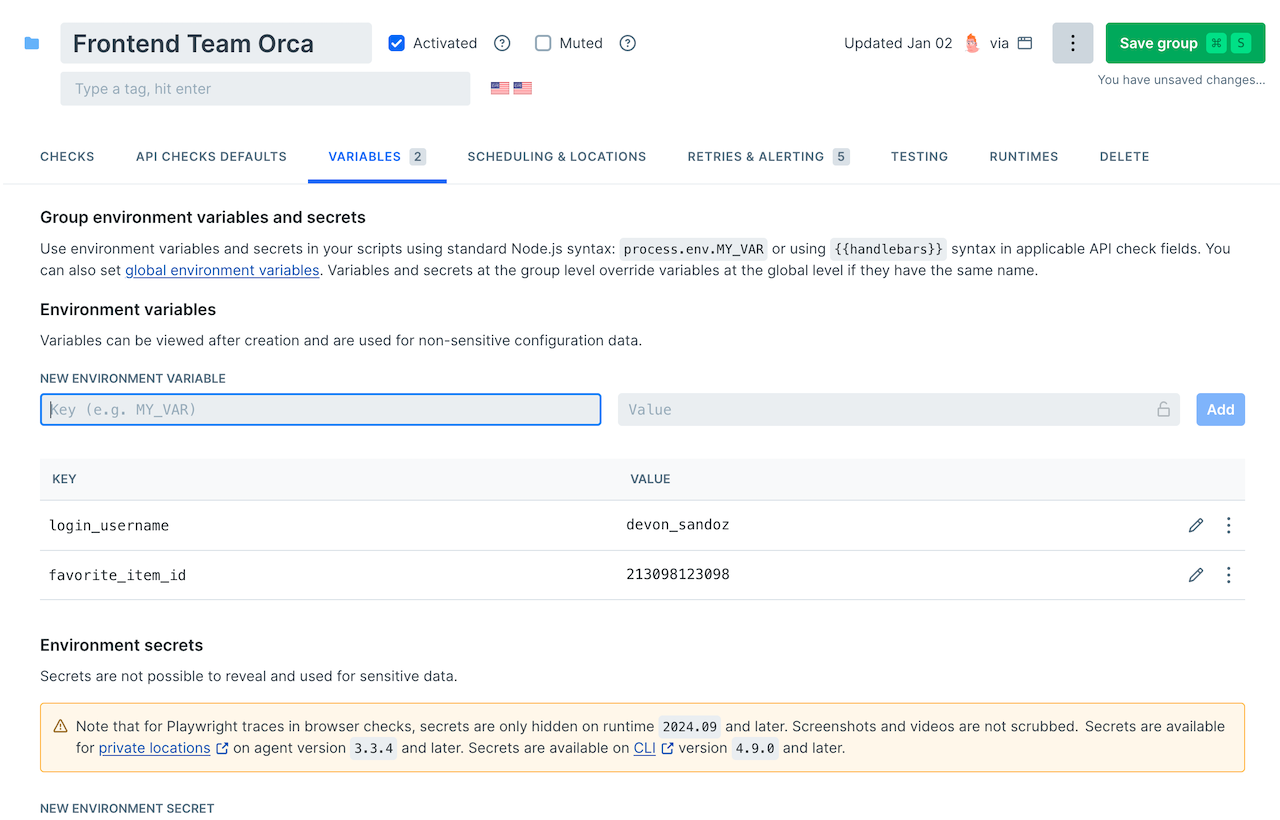

These are all goud reasons to create a check group. Groups have their own set of variables and configuration for all the members of that group. Checks can be added to a group either by configuration at the code level (passing a checkGroup object to the config), or in the web UI by creating a group and clicking ‘Add Checks to Group’.

Setting variables that will be available to every check in this group

Some important things to remember when working with a group of checks:

- Alerts go to the groups alert channels, so be sure your group is connected to at least one alert channel or you will miss any notifications from this group!

- Checks in the group are run individually, not as a group. If you’re thinking of doing something like a post-run cleanup with a single check for the whole group, that won’t work as expected, instead run cleanup scripts individually for each check.

- For API checks, you can have a ’teardown script’ for a group that runs after every check is completed.

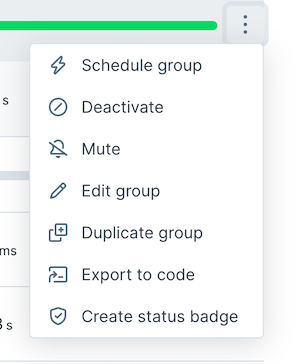

- That said, all the checks in a group can be triggered to run at the same time, this is especially useful if a group is used to run checks after deployments.

Running a group from the Web UI's 'Schedule Group' option

- Any settings that are given in two places will be reconciled with the following heirarchy:

- individual settings on a check

- group settings

- global settings

So group settings will override global settings, and individual settings will override everything else.

- While groups are a useful feature of Checkly, and will make sense for some applications, you may also be served by using Javascript and Typescript’s native features for inheritance. Since files can inherit modules from others, it’s possible to share configuration very cleanly, is as complex a heirarchy as you’d like, using these native features. This especially may make sense if you’re going deep into Monitoring as Code and want to set up a complex repository for all monitoring. Native features also help support the next section on using fixtures to share code blocks.

Sharing code for repeated tasks

While there are sophisticated ways to share authentication across checks discussed in other guides, it’s good to know how to share code with fixtures for common repeated tasks. Let’s imagine an example where we’ve got a web shop with a login modal that we need to fill out before doing further account actions. The goal of my check isn’t really to test this modal, it just needs to be filled out before my real testing, where I look at my demo user’s recent orders:

To open this modal and log in, we might use some lines like the following:

import { test, expect } from '@playwright/test';

test('display Recent Orders', async ({ page }) => {

await page.goto('https://danube-webshop.herokuapp.com/');

await page.getByRole('button', { name: 'Log in' }).click();

await page.getByPlaceholder('Email').click();

await page.getByPlaceholder('Email').fill('robert@moresby.com');

await page.getByPlaceholder('Password').click();

await page.getByPlaceholder('Password').fill('@!#KLjwsWe4@');

await page.getByRole('button', { name: 'Sign In' }).click();

// Here's my actual test code to check my orders

});

This is a fine practice for a single test, but if we have dozens that all require login as a first step, we’ll find ourself copying and pasting this code several times. This means a lot of copied code, such that if we ever tweak the login process, we’ll have to update this copied code in dozens of places, not good!

We’d want to move this code into an extension of the Playwright page fixture like so:

import { test as baseTest, expect } from '@playwright/test';

const test = baseTest.extend({

userPages: async ({ page }, use) => {

// Your setup logic here

await page.goto('https://danube-webshop.herokuapp.com/');

await page.getByRole('button', { name: 'Log in' }).click();

await page.getByPlaceholder('Email').click();

await page.getByPlaceholder('Email').fill('robert@moresby.com');

await page.getByPlaceholder('Password').click();

await page.getByPlaceholder('Password').fill('@!#KLjwsWe4@');

await page.getByRole('button', { name: 'Sign In' }).click();

console.log('setup');

// After logging in, pass the `page`

// object to the test cases

//

// Whatever you call `use` with

// will be available in your test cases

await use(page);

// Teardown logic, if any

console.log('teardown');

},

});

//Now we can use that userPages object repeatedly

test('display recent orders', async ({ userPages }) => {

// any code added here can make normal expectaions of the page!

});

test('cancel recent order', async ({ userPages }) => {

// any code added here can make normal expectaions of the page!

});

In this example, we’ve just put our fixtures at the top of a single check’s file, and shared it across tests within that file, in the next we’ll share a code snippet across multiple files, and running code with every check.

See it in action: Reuse Playwright Code across Files and Tests with Fixtures

To see fixtures demonstrated, and a step-by-step explanation of the code, check out Stefan’s tutorial video:

Running standardized code across every check

While it’s useful to package up tasks like logging in across multiple tests, we may want some code to run before and after every single check. Some possible examples:

- We know that every session has to set the same page settings every time (like cookie settings)

- Manually cleaning up any test’s actions - for example restoring our demo user’s account settings

For these, again, we could use core Javascript/Typescript modules to accomplish this task, here’s an example

import {setup, teardown } from "./standardScripts.ts"

test.beforeEach(() => {

setup();

});

//add tests here

test.afterEach(() => {

teardown();

});

But while it’s great to use native features, this is requireing a good amount of setup in each test file (the above snippets would have to be repeated in each new file), and our goal is to make creating new checks as easy as possible for developers. So let’s use Playwright’s native features to make this even easier for them.

import { test as base } from '@playwright/test';

export const test = base.extend<{ forEachTest: void }>({

forEachTest: [async ({ page }, use) => {

// This code runs before every test.

console.log('test is about to start! setting up');

await use();

// This code runs after every test.

console.log('test finished! cleaning up');

}, { auto: true }], // automatically starts for every test.

});

Now the only change you’ll need to make to your test files is to have them import the test function from this fixture file, for example:

import { test } from './testFixtures';

import { expect } from '@playwright/test';

See it in action: running code before and after every check

To see this demonstrated, and a step-by-step explanation of the fixture code, check out Stefan’s tutorial video:

Here’s our complete YouTube playlist on fixtures.

Conclusions

Simplifying monitoring processes through automation and standardized practices allows developers to focus on what matters: ensuring their services function as intended. By leveraging tools like the Checkly CLI and adopting practices like Monitoring as Code, reusable fixtures, and standardized configurations, teams can involve developers in monitoring without overwhelming them with setup complexity or configuration details.

These strategies reduce repetitive work, enable consistency across tests, and ensure that monitoring integrates seamlessly into the development workflow. Ultimately, this approach promotes a culture of shared responsibility for reliability, making it easier for developers to contribute to the stability and observability of their systems without needing deep expertise in monitoring tools. With these methods, teams can improve collaboration and maintain a robust monitoring setup that scales with their needs.